Montessori: Not Just a Way of Teaching

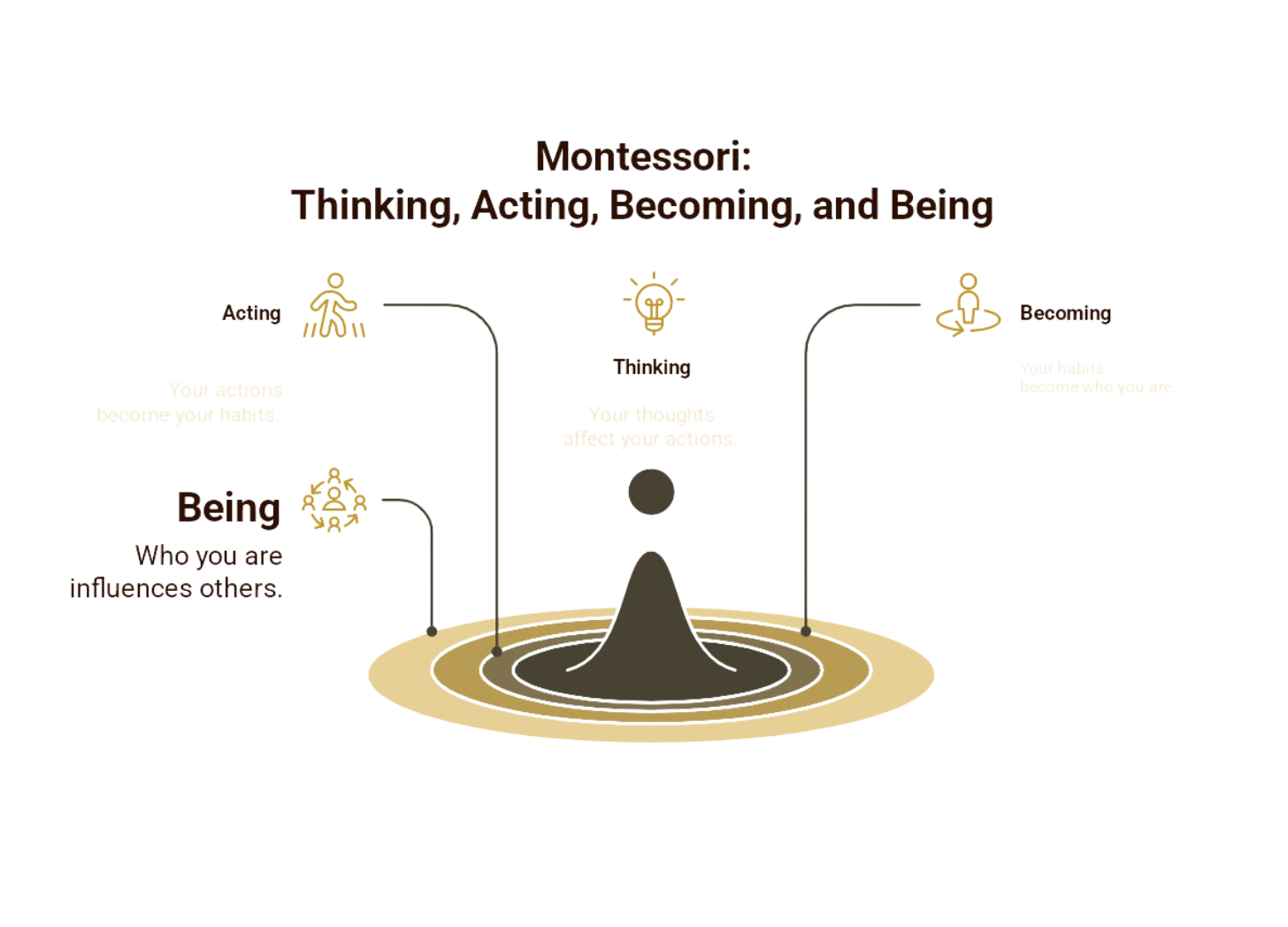

It's a way of thinking, acting, becoming, and being

Have you ever been confronted and challenged by someone's life-changing ideas?

That happened to me. Dr. Maria Montessori’s thinking flipped my world, made me a better mom and a better person. In this newsletter, I'll be sharing with you stories from my journey of becoming and being a Montessori adult.

Continue reading below . . .

Montessori: a Way of Thinking (Learning what principles to hold)

Living in 4 out of 5 American garages, you'll likely recognize WD-40's familiar can with its primary colors of blue, yellow, and red. But did you know that the name stands for "Water Displacement perfected on the 40th Try"? (Emphasis mine, just wow)

While most people recognize Montessori by its pedagogical materials like the Pink Tower and the Cylinder Blocks, fewer people are aware of Montessori principles. These ideas were developed over time as Maria Montessori observed the behaviors of multitudes of children from across the socioeconomic spectrum. One such principle is Friendliness to Error.

The first time I heard that phrase from my Montessori mentors, I was stunned. Never before in my life had I thought about error as something to be friendly toward. Growing up Asian, error was the Enemy-to-be-Avoided-at-All-Costs, the obnoxious, mocking, ugly billboard that screamed "You failed!" Why in the world, and more importantly how, could I ever be friendly to error?

After I understood the why behind Friendliness to Error, I embraced the principle immediately. Error is a teaching tool, an opportunity to figure out why something didn't work, to narrow down the possibilities of what may work in the future. The process behind every invention that has survived the brutal, unforgiving test of time, like the light bulb, the airplane, and WD-40, is the result of the inventors learning from their mistakes and pushing forward to a better result. I already knew this from an intellectual perspective. But the phrase Friendliness to Error was truly an idea I could wrap my mind around — to me, it was succinct and perfect.

I wanted my children to grow up with this attitude precisely because it was an attitude that I didn't have growing up. This phrase helped 28-year-old me start to acknowledge my own brokenness, the spoils of my war against error. Truth be told, I still battle the effects of this deficiency decades later.

Montessori: a Way of Acting (Behaving according to those principles)

A former colleague of mine was the poster child of Paralysis by Analysis. This lady was very bright and loved to research, to find the best possible way of doing something. Incredibly high standards. A wonderful example to others. Sounds great, right?

The problem, though, was her belief that there actually was only ONE. WAY. to do something. And boy howdy, she was going to find that one way. Life, though, has shown that there are often many successful ways of accomplishing the same task. Because she was so focused — dare I say obsessed? — with getting something perfect the first time through that one way, this person wasn't even willing to learn from mistakes. She had total disdain for mistakes. And because of that, she rarely finished projects, not able to get past the research and analysis stage.

This woman's self-constructed trap prevented her from acting, and this made a deep impression on me. Her example was why the idea of Friendliness to Error instantly clicked for me. I could see in her the extreme harm and cost of not being friendly: staying stuck. Accepting the why, however, was much, much easier than figuring out the how to put Friendliness to Error into practice.

The first step to any real change is desire. And I intensely wanted to become friendly to error. I began with teeny, wobbly baby steps, like literally biting my tongue and swallowing my impatient, sharp words while watching my two-year-old struggle to put on gloves "by my ownself". There were even times when I sat on my hands to prevent myself from snatching something away from my child. Yes, I could do it better, but that wasn’t the point. The point was to give my child room to struggle, which was really room to learn and grow.

Continue reading below . . .

Montessori: a Way of Becoming (Turning the one-off actions into a habit)

Habits are like a wall that we build, brick by brick, slowly around ourselves. These walls can be protective and therefore good, like habits of physical exercise and punctuality. Or these walls can be destructive and thus inhibiting, like mentally beating ourselves up for unintentional mistakes or resorting to emotional, unhealthy eating. (A tangent thought: is there such a thing as an intentional mistake? Well, yes, for a specific purpose. Stay tuned for a future article.)

We often start building these habits when we are young, imitating the examples given to us by our families. That's why it was so important to me to encourage my children to develop Friendliness to Error. I wanted to break the generational chain of seeing Error as an enemy. This meant that I had to go beyond being friendly to my old enemy every so often — I had to actually become and be truly friendly.

I had to set the example, which meant I had to change myself. I began actively looked for situations where I could be friendly to error: both error in myself and error in others. Failing to defrost something in time for dinner became the impetus for me to get better at meal planning. Instead of assuming the jerk . . . er . . . guy purposely cut me off in traffic, I gave him the benefit of the doubt that maybe he just didn't see me.

Montessori: a Way of Being (Affecting others)

Changing myself gave me credibility with my children when I encouraged them to not let their frustration over small things devolve into anger. Gradually, my children became kinder to their siblings and friends.

Embracing Friendliness to Error has had a positive ripple effect. Montessori’s principle was the drop in my mental pond, which started clearing out my own head trash. That effect moved outward to my children, our family life, and our wider social circles. I couldn’t have foreseen the result: my thoughts metamorphosed into influence.

Montessori: the Way of Teaching as the natural outcome of Thinking, Acting, Becoming, and Being

I'll never stop marveling at the genius of Maria Montessori.

She thoroughly grasped the development of the human person precisely because her understanding was rooted in observations of the children in her care — the same way the Scientific Method works. She didn't impose an ideology of what she thought children should be. She observed the children just as they were and then provided for their psychological and developmental needs accordingly.

For instance, Montessori observed that the children delighted in figuring things out for themselves. Sensitive to this, Montessori designed many of her pedagogical materials to have an internal Control of Error — the material would do the teaching. (This is why, in Montessori environments, the adult in charge is not called a teacher but a Directress or Guide.)

An example of this are the Cylinder Blocks. Created to teach the concepts of height and diameter, it is physically impossible for the wrong cylinder to fit properly in a space. While trying to figure out which cylinder goes where, the child is learning and practicing:

perseverance and patience > to keep trying

independence and initiative > to figure it out on one's own

creativity and confidence > that given enough effort, things will work out

Without an attitude of Friendliness to Error, the child would just give up in frustration.

At its core, Montessori is truly a way of Thinking, Acting, Becoming, and Being, which takes a concrete form in its way of Teaching. Through Montessori, one can learn:

what principles to hold

how to act according to those principles

how to turn those single acts into a habit of being

and then to be a gentle, subtle force of influence on others.

I broke the generational chain of my captor Error-as-Enemy through joining the links of better Thoughts, Actions, Habits, and Influence.

Having read dozens of books in my favorite genres of personal development, productivity, and business, a huge takeaway for me is how many struggles would be resolved by becoming and being a Montessori adult. I'll be covering these topics in this newsletter.

In my next article, I'll talk about how Music and Montessori are better together.

P.S. During my final edit of this piece, I was struck by this thought: embracing Friendliness to Error has brought me to a mind place where I am now much friendlier to myself. I no longer talk to myself in a harsh way, lashing out with, “What an idiot I am,” or “Gosh, I’m so stupid”.

Maybe you’re nicer to yourself than I was. But if you find you need to become friendlier to yourself, try giving Friendliness to Error a hug.